Michael-David Mangini

Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations

University of Southern California

Previous

Harvard University

Princeton University

Yale University

Biography

I am an Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Southern California. I graduated from Harvard University with a Ph.D. in Political Economy and Government in 2022. I was previously a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Niehaus Center for Globalization and Governance at Princeton University and a Postdoctoral Associate in Political Economy with the Leitner Program in Comparative and International Political Economy at Yale University. Before graduate school I worked in economic consulting and I graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 2014. My research primarily studies economic coercion and the international political economy of trade, but I also have interests in state formation and the politics of structural transformation.

Download my CV.

BA in International Relations and Economics, 2014

University of Pennsylvania

PhD in Political Economy and Government, 2022

Harvard University

Publications

Working Papers

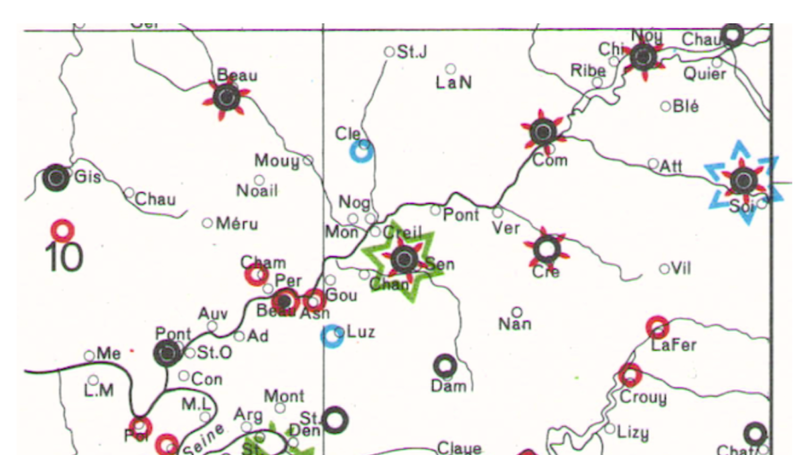

We argue that the gunpowder revolution in medieval Europe encouraged the amal- gamation of smaller polities into larger centralized states. The advance in military technology made existing fortifications obsolete and substantially raised the cost of defensive investments. Small polities lacked the fiscal capacity to make these invest- ments, so they had either to ally or merge with others. Alliances created prospects of free-riding by interior cities on border cities. In contrast, centralized, territorial states benefited from geographic and fiscal economies of scale, facilitating defensive invest- ments at the border that protected the interior while limiting free-riding and resource misallocation. Using a new dataset on fortifications in 6,000 European cities, we find that states made defensive investments in areas of territorial contestation, closer to borders, and farther from raw building materials. These findings are consistent with our theory that large centralized states arose in part as a consequence of changes in military technology.

Teaching Experience

Contact

- michael-david.mangini@yale.edu

- New Haven, CT 06511